You cannot pick up a newspaper, click on a website or listen to a podcast these days without learning of another biomedical science breakthrough. New treatments are driving mortality rates downward for diseases such as AIDS/HIV and cancers that just a few years ago would have been considered almost assuredly fatal. And just over the horizon are even more promising therapies for illnesses and chronic afflictions.

In 2014, the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) recorded over $51 billion of R&D investment resulting in more than 7,000 potential treatments that are filling the new drug pipeline. The White House has certainly taken notice; as far back as 2012, it released the President’s National Bioeconomy Blueprint calling attention to the sector’s “tremendous potential for growth as well as the many other societal benefits it offers.”

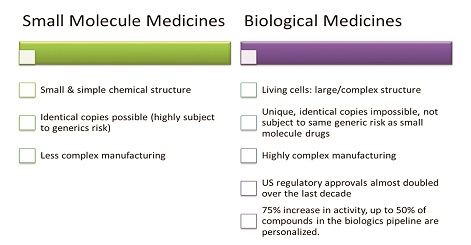

While the administration’s roadmap focused on all facets of the bioeconomy, here our emphasis will be on the biopharmaceutical industry that has grown up around the treatment of disease. The two sectors within this industry include:

-

The so-called “small molecule” traditional medicines which are derived from chemical synthesis. These are the most familiar type of medicine compounds, typically contained in a pill, tablet or capsule. Examples range from analgesics and other pain relievers to antibiotics, antidepressants and antihypertensives.

-

The newer biological or “large molecule” medicines derived from living organisms, including therapeutic proteins, DNA vaccines and monoclonal antibodies. These biologic drugs are often far more complex (and more challenging to manufacture, store and transport) than their small-molecule cousins.

The societal benefits notwithstanding, it would be difficult to overlook the significance of the bio-pharma industries to the U.S. economy – hence the sector’s attractiveness to state, regional and local economic developers. The Battelle Technology Partnership Practice, in a report recently prepared for PhRMA, highlighted some of the most material benefits:

-

The 2013 national bio-pharma annual wage ($110,000) was more than twice the U.S. average

-

More than 800,000 direct jobs are supported by the industry and another 2.5 million jobs exist among the sector’s numerous vendors and suppliers

-

In 2011, the industry created approximately $789 billion of wealth within the U.S

-

The aforementioned $51 billion of R&D spending (much of which is directed at universities and research institutions) has boosted local investments in STEM education.

That having been said, bio-pharma companies also find themselves confronting unprecedented new challenges even during this period of growth and innovation. These include the cost pressures resulting from the Affordable Care Act and the growing influence of insurance companies that have begun mandating “value-based” payments for patient care (as opposed to the long-standing fee-for-service basis) and pushing back with drug “black lists” and mandated generic substitution. Additional pricing constraints are being felt from the rise of consolidated buying groups (hospital chains, HMOs and chain pharmacies). All the while, pharma company earnings have taken a pounding as blockbuster drugs go off patent and generics rise. Thus, the variables governing so much bio-pharma location decision-making today tend to reflect the sometimes conflicting dynamics of this new reality: accelerate innovation while reducing the time and costs associated with bringing a new drug to market.

While their influence over the location decision process will vary depending on the nature of the project (headquarters, R&D operation, biologics manufacturing facility, etc.), site selectors and economic developers would do well to heed the following critical success factors as they make their plans to locate or attract valuable new life sciences jobs and investment. The leading biologics clusters generally develop in a region with:

-

Strong research institutions

-

A highly skilled and mobile workforce

-

Access to a constantly renewing supply of talent

-

Availability of capital

-

An attractive quality of life.

Depending on the specific activities to be performed, other significant locational variables can include: available and appropriate sites and buildings, a transparent and predictable regulatory environment and available supporting services and effective incentives.

Research Institutions

The largest pharma companies are increasingly relying on partners to help fill their drug pipeline with promising compounds. Some of the biggest companies now spend 20 percent of their budgets on partnered R&D (Merck has 75 partnerships, Lilly more than 100). This can be facilitated by proximity to smaller drug companies that possess the speed, inventiveness and entrepreneurial talent often absent or greatly diminished in many of the larger enterprises. Of course, these same companies also are attracted by the ability to collaborate with the most agile research universities that continue to develop and move discoveries into the marketplace.

Skilled Workforce

Of all locational determinants, talent may be the variable most influenced by the specific activities comprising a biopharma project. A quick survey of the various functions and relevant sample job titles reveals this diversity:

No matter white collar or blue, highly capable workers who are able to frequently and quickly master new skills will be very much in demand.

No matter white collar or blue, highly capable workers who are able to frequently and quickly master new skills will be very much in demand.

Talent Pipeline

Staffers retire, relocate, change careers or defect to other companies, putting a premium on the pipeline of new talent. While an attractive destination (think Cambridge, San Francisco or Raleigh-Durham) will benefit from continual re-supply via in-migration, most bio-pharma markets are forced to rely on their own assets for the replenishment of talent. At the forefront are the post-secondary educational institutions arrayed across a region. These include the local two- and four-year colleges and universities that produce the marketers, JDs and MBAs needed to manage corporate strategy and governance; the Ph.Ds. in microbiology, immunology, pharmacology and toxicology recruited to staff the laboratory benches; and the newly minted workers with associates degrees in bioprocessing, electromechanical engineering and instrumentation hired to keep modern biologics plants humming. The farsighted site selector will go one step further, however, and also investigate the state of the local K-12 educational system because it’s a known fact that the U.S. is graduating an insufficient number of high school students with grounding in the technical disciplines and thus little or no interest in STEM careers. The best school systems tend to be those that engage students early by:

-

Requiring proficiency in 8th grade math and science

-

Offering a selection of AP-level coursework in high school

-

Requiring biology as a condition of graduation

-

Demanding that science teachers actually have science degrees.

Risk Capital

Despite a strong IPO market for life sciences companies and rising valuations for private company acquisitions, it is becoming more difficult for bioscience startups to raise financing as investment shifts to later‐stage deals. This challenging environment may not directly impact the biggest companies whose announcements frequently comprise some of the year’s “trophy” projects. However, because it can (and often does) thwart the growth of local gazelles (those most nimble and entrepreneurial of companies), it has serious implications for the local innovation eco-system. To address this gap, some state governments now offer tax incentives to catalyze private investment in venture capital funds and/or in technology‐based companies and also by investing public funds directly in private venture capital funds or companies.

Quality of Life

Life scientists are the new “rock stars” recruited with the same zeal that would drive a major league baseball team to sign a Cy Young award winner. A renowned researcher or principal investigator can establish his or her lab almost anywhere; what they prefer are places featuring:

-

Quality school systems

-

Desirable neighborhoods

-

Abundant entertainment and recreational opportunities;

-

Easy access to the rest of the world

-

Moderate costs of living.

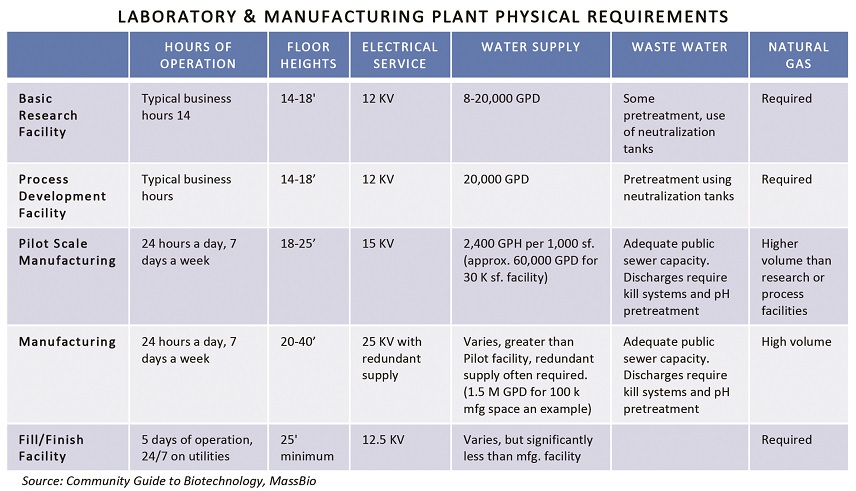

Appropriate Space/Sites

While some markets are experiencing a long-term oversupply of life sciences space, many others vying for projects have an inadequate inventory of suitable facilities or development-ready sites. These markets also are handicapped by the absence of builders who know how to profit by addressing the arcane requirements of life sciences companies. Competitive advantage will accrue to those places that have (or can quickly supply):

-

“Certified sites” or properties with fully approved site plans

-

Fully permitted shell buildings

-

Wetlabs

-

Vivariums

-

Incubators and accelerators with variety of lab/office suites, common equipment or core lab facilities and professionally appointed meeting/training space.

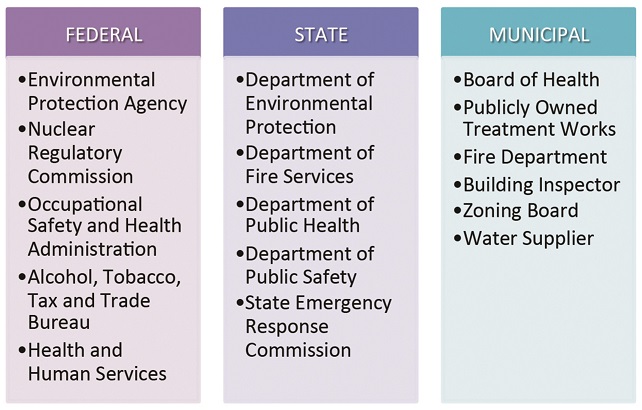

Bio-pharmaceutical companies typically face a gamut of local, state and federal regulations to bring an R&D or manufacturing project online. A recent Massachusetts engagement involved review and permitting by no less than 16 regulatory bodies.

At the municipal level, the most competitive destinations will feature sites or buildings pre-permitted for life sciences users and a specially appointed (and industry-knowledgeable) ombudsman to help expedite these types of projects. At a minimum, any community courting pharmaceutical and biologics projects should offer transparent and predictable approvals processes and timelines that take into account the particular requirements of the bio-pharmaceutical industry. This could mean master plans and zoning ordinances that allow for bio-pharma laboratory and manufacturing uses by right, concurrent subdivision and site plan approval, and the latitude to interpret and apply building and fire codes with biomedical users in mind.

At the municipal level, the most competitive destinations will feature sites or buildings pre-permitted for life sciences users and a specially appointed (and industry-knowledgeable) ombudsman to help expedite these types of projects. At a minimum, any community courting pharmaceutical and biologics projects should offer transparent and predictable approvals processes and timelines that take into account the particular requirements of the bio-pharmaceutical industry. This could mean master plans and zoning ordinances that allow for bio-pharma laboratory and manufacturing uses by right, concurrent subdivision and site plan approval, and the latitude to interpret and apply building and fire codes with biomedical users in mind.

Suppliers

Local vendors of products and services that support laboratory and manufacturing operations are a hallmark of mature biopharma clusters. These can range from the mundane — suppliers of clean room materials such as sterile filters, lab media and gowns to the specialized — maintenance companies familiar with GMP (sterile) environments and staffing agencies dedicated to GMP skills to the esoteric — validation consultants who help prepare and execute quality protocols and FDA compliance documentation for equipment, utilities, processes, laboratory instruments and computer systems.

Incentives

Incentives are pricing tools that can put job-generating and capital-intensive projects such as bio-pharma facilities on a more sound financial footing. As such, they are an important economic development strategy in those markets targeting life sciences jobs and investments. Among U.S. states with a significant pharmaceutical industry presence, New Jersey has been an innovator and a highly aggressive user of incentives. For example, the Grow New Jersey Assistance Program uses transferable tax credits that can range as high as $8,000 per job per year in certain communities to attract or retain corporate investment. Monetizable job creation tax credits such as Grow New Jersey, along with cash grants for job creation are a common economic development strategy among popular biopharma states, as are programs that offer exemptions from state sales and use taxes on equipment used in R&D and biomanufacturing. Again, New Jersey goes further than most, even offering startups the opportunity to sell their net operating losses for at least 80 percent of their value through the innovative Technology Business Tax Certificate Transfer program.

In conclusion, the best locations are those that help execute corporate strategy by providing the optimal mix of attributes while also helping to manage costs and risks. During site selection there is no substitute for making an informed and transparent location decision that balances the needs and wants of all stakeholders. Communities wishing to attract investment and jobs from the bio-pharma industry should first take a hard look at their assets and shortcomings to determine whether they have what it takes to compete.