What’s more, global commercial aviation passenger revenue miles grew at 7.6 percent in 2017 – that’s more than double the rate of global GDP growth. In addition, commercial aviation grew above six percent the two preceding years and above five percent each year since the Great Recession of 2008/2009. Boeing forecasts the new equipment market to consist of more than 40,000 large commercial aircraft over the next 20 years, at a value of $6.1 trillion.

The U.S. is also the world’s leading exporter of defense equipment. The Trump administration is emphasizing growth in U.S. defense exports and the easing of restrictions on defense exports, including drones. In 2017, President Trump visited Saudi Arabia and announced $100 billion in new defense exports. In addition to the Middle East, there is increased export activity in Asia, in response to the military modernization of China as well as the North Korean threat. The U.S. is also seeing resurgence in demand for defense equipment from European countries, partly in response to a more aggressive Russia.

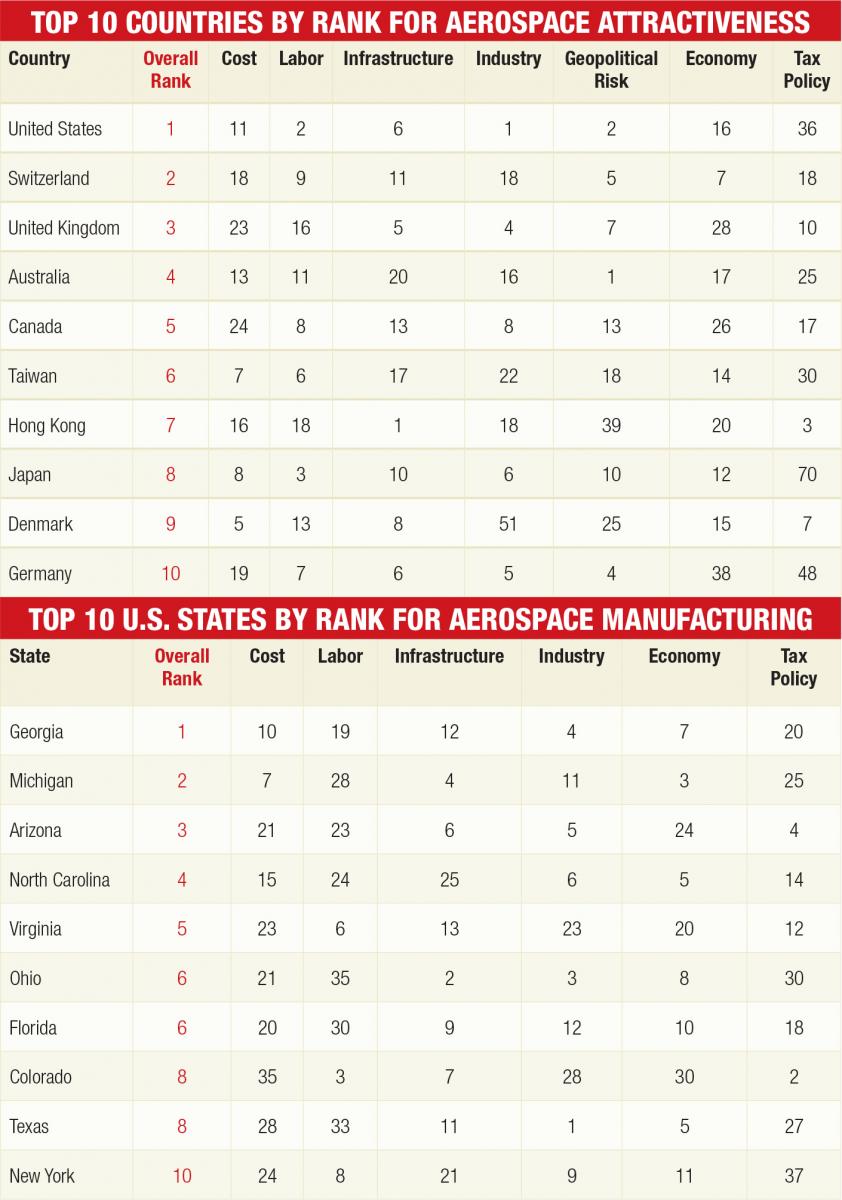

With such growth, where should manufacturers consider for corporate site development and expansion? One place to find the answer is the PwC annual global and state-by-state review of aerospace manufacturing attractiveness, an aerospace industry review it began performing in 2013. PwC’s initial analysis included extensive interviews with industry executives. Over the years the company has refined its methodology. Its analysis now examines metrics in the following categories:

• Cost – Six metrics that include labor cost, labor productivity, energy and transportation costs

• Labor – Five metrics, including the size of the A&D workforce, education categories and union flexibility

• Infrastructure – Includes five metrics related to energy, roads, airports, railroads and Internet

• Industry – Includes six metrics related to the size, growth and maturity of the industry

• Economy – Includes six metrics related to size, growth, inflation and subsidies

• Tax policy – Includes six metrics related to corporate and individual income tax, sales and property taxes

• Geopolitical risk – For the country analysis, PwC uses metrics related to political stability, corruption and natural disasters.

In its rankings, PwC weighs each of these categories equally. However, it emphasizes that each user of its analysis may weigh these categories differently, thus the analysis can be tailored to each user. The 2018 report will be published in late June, early July. The 2017 results follow.

Country Analysis

Country Analysis

Within the top 10 countries, there are a few surprises. That’s because many people think only in terms of industry size. The U.S., U.K., France, Germany, Canada and Japan are known for their aerospace prowess. When considering all the factors in its analysis, however, several surprises emerge. Switzerland, Australia, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Denmark are competitive across the board, despite having moderate or small industry ranks. Also noteworthy, while China did not make the top 10 overall list, China is now No. 2 in industry rank, as the country has invested significantly in developing a domestic aerospace industry and including foreign investment such as Boeing’s and Airbus’ assembly lines.

United States

The United States consistently places first in the aerospace manufacturing rankings, partly as a result of the aerospace industry’s significant scale, supported by a relatively strong economy, robust air transportation infrastructure and active defense posture. Within the Industry category, the United States was first in industry size and maturity, as the U.S. continued to have the highest proportion of global aircraft deliveries and defense spending. Accordingly, the U.S. performance in Industry far exceeded that of other countries in the analysis. The United States also placed high in the Labor, Geopolitical Risk, and Infrastructure categories.

However, the U.S.’ strong performance across all metrics does not reflect some of the underlying risks to maintain industry leadership.

• Tax policy

The U.S. ranked 38th in tax policy in 2017 and ninth among the top 10 countries. The U.S. is sure to get a big boost in tax policy ranking as a result of tax reform taking effect in 2018. While tax reforms have made the U.S. a leader in tax policy, the extent of advantage could be temporary, as many countries are considering a competitive response. While a competitive response could reduce the U.S.’ current advantage, it is unlikely the U.S. could become disadvantaged by any reforms that may occur in other countries.

• Labor

While the U.S. ranked second in labor, the ranking is based largely on the size of the aerospace and defense workforce and strong productivity. The U.S. still has a significant skills gap, though, as well as a demographic gap.

The demographic gap facing the U.S. aerospace and defense industry is sometimes referred to as the “lost generation.” A significant number of Baby Boomers are retiring in the coming years without an adequate bench of Generation Xers to replace them. The concern is particularly acute among engineers and skilled manufacturing talent at defense companies, which reduced their workforce and cut back on hiring in the years between the end of the Cold War in 1991 and the start of the war on terror 2001.

Recent years have borne witness to some success in public/private partnerships between industry and universities to address the skills gap. Yet, as the digital age widens the gap, efforts in this area need to double. This requires greater participation by federal and state governments, which may need to include immigration reforms designed to bolster critical skills.

While the U.S. ranked sixth in infrastructure, many people believe the U.S. has significantly underinvested in infrastructure and that much of the country’s infrastructure is badly in need of repair or replacement. In particular to the aerospace industry is the next generation air traffic control (ATC) system, designed to make aviation safer, more reliable and efficient. The system is particularly important to improve capacity in saturated markets and allow for continued growth. The next-gen ATC is the implementation of dozens of new technologies, including GPS tracking to replace the radar-based ground system. Additionally, many of the nation’s airports are in need of modernization to accommodate current volumes and allow for growth, as well as improving the consumer experience.

Beyond aviation infrastructure, many of the nation’s roads, bridges and railroads are in need of modernization to allow the aerospace supply chain, as well as many other industries, to operate efficiently and support growth. Given the practical limitations associated with the federal and state budgets, greater private funding and tolling could work in many instances to improve the state of the nation’s infrastructure.

• Cost

While the U.S. is fairly competitive in cost, ranked 11th, energy will be a strategic differentiator in the future. As the world seeks “greener” energy sources, the countries that can develop and implement these new energy sources in a cost-effective manner will create competitive advantage. Furthermore, while some companies have historically generated some of their own energy needs, new technologies mean companies are less reliant on the grid than before. In fact, many experts believe the future of energy is distributed power generation. Already, some companies are using a combination of technologies including solar and wind to generate some of their energy needs.

• Innovation

The most important aspect to future competitiveness is, of course, innovation. Innovation is not measured in the PwC analysis partly because innovation metrics are hard to find, but also because innovation is seen as more specific to individuals or a company rather than geography. Surely, though, governments have influence over innovation. Many of the world’s leading industries were developed as a result of research for defense and space programs, such as computers, the Internet, GPS and many telecommunications applications. Tomorrow’s innovations will be digital, particularly in the area of artificial intelligence. Some governments, such as China and Russia, are strategically investing in these areas of innovation. With big technology companies far outspending the government on R&D, federal funding is, perhaps, less critical than it was during the space race. However, strategic government spending in areas such as artificial intelligence is still critical to national security and competitiveness and should be a priority.

There are a number of strategic decisions and investments for companies to make to drive innovation, as well as critical policies and investments for federal and state governments and public institutions to ensure that the U.S. remains the leader in aerospace and defense, and which also benefit many industries. These include:

• Investment in digital technologies, particularly artificial intelligence

• Investment in the workforce of the future, particularly digital skills

• Investment in the nation’s infrastructure, particularly next-generation air traffic control

• Investment in clean, affordable energy.

The companies and countries that can create competitive advantage in these areas will be tomorrow’s leaders. T&ID

Sullivan Networks Partnership, TN:

Northeast Section of Tennessee a Strong Supporter of its Aerospace Cluster

The aerospace cluster within the Sullivan Partnership region in the northeast section of Tennessee remains strong, with most companies doing very well and growing. The area is proud to be the place that Bell, Eastman, Wysong, Aeronautical Accessories and BAE Systems, just to name a few, call home.

The region is actively developing and growing the workforce needed to support its aerospace cluster. Northeast State Community College’s aviation program remains at capacity and the college recently announced partnership with nearby Milligan College and the Tennessee College of Applied Technology. The Regional Center for Advanced Manufacturing (RCAM) has expanded and added a unique apprenticeship program to better serve all of its manufacturers.

Really exciting developments have also taken place. Two counties and three cities have invested more than $8 million into the development of 167-acre Aerospace Park, and the State of Tennessee has contributed over $4.5 million through Department of Transportation and Department of Economic and Community Development grants. Sullivan Partnership has also received another $1.5 million in grants for two other sites. It continues to make investments that will lead to aerospace and other advanced manufacturing opportunities.