While the extraction of gas and oil via hydraulic fracturing is helping create wealth and prosperity in many parts of our country, it is also creating challenges for local communities, governance, site selectors and the oil/gas industries.

The greatest challenge for communities lies in how to utilize wealth generated today to build sustainable future economies. At the same time, companies and site selectors also experience challenges when working with local zoning and planning entities. In many cases, the rapid increases in permit applications and needed changes in land use coupled with local limitations in expertise and staffing slow local and county action in the site selection and development process.

In many regions of the country, a great deal can be learned about sustaining today’s opportunities by observing their past. Many communities were created by natural resource extraction. Coal, iron ore and clay mining produced jobs, attracting people to settle in the region. At that time, socio-economic structures, such as charitable foundations or economic development organizations, had not yet been developed. Today, such organizations retain a portion of the income flowing through their communities for reinvestment in the future.

In many regions of the country, a great deal can be learned about sustaining today’s opportunities by observing their past. Many communities were created by natural resource extraction. Coal, iron ore and clay mining produced jobs, attracting people to settle in the region. At that time, socio-economic structures, such as charitable foundations or economic development organizations, had not yet been developed. Today, such organizations retain a portion of the income flowing through their communities for reinvestment in the future.

Over time, extraction will slow and well production will cease to be economically viable, yet communities will continue to require public services such as educational institutions, housing, public safety, governance and physical infrastructure.

Early Recognition of Challenges

Since the 1970s, extraction of shale oil and natural gas in the United States has become one of the most significant emerging industries in recent years. Deposits are proving to be both an asset and a challenge to local governmental structures.

This is particularity true because the deposits are located in thinly populated rural areas where governing entities possess limited resources, staffing and expertise.

The impact of rapid growth, workforce requirements, land use, zoning and housing, etc., are stressing many local jurisdictions’ ability to provide services and maintain the economic fabric of the community.

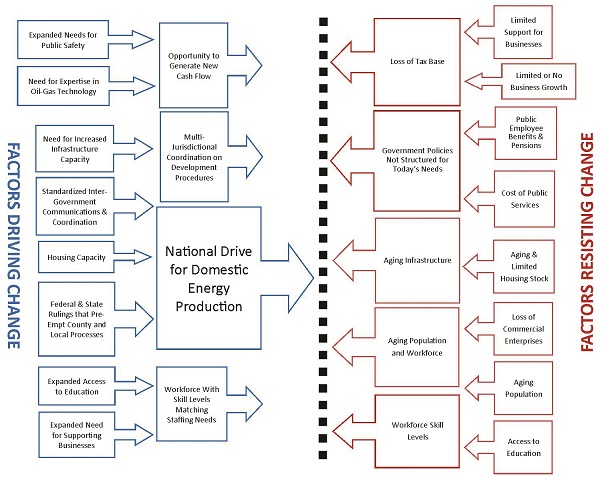

Most governments are only beginning to sense the unanticipated impacts of hydraulic fracturing on their communities. In many instances, the landscape of issues is in conflict with existing processes. A force field analysis can provide examples of where conflicts may occur.

Crucial Forward-Planning Areas

Crucial Forward-Planning Areas

Local governments in areas where economic and staff resources are not present or in limited supply are those in most need of forward-planning. Site selectors need to be keenly aware of this need when considering development in these areas.

This planning process relies on frequent assessments and re-assessments of local conditions and areas of impact. Forward-planning is particularly effective when the factors driving change require new policies and capital projects. Repeated benchmarking assessments should be conducted on not less than a 24-month schedule, with a full assessment conducted every five years.

Examples of impact areas for which forward-planning may be necessary include:

-

Roads and Highways: One of the largest budget line items is that of the road/highway departments. Damage to local and county roads by heavy truck traffic carrying from 800,000 gallons to four-million gallons of water per well simply wears out road surfaces and roadbeds.

-

Emergency Care: County/town emergency and health-care services will experience increased demands. This can be due to the increase of on-the-job injuries.

-

First Responders: Fire-fighting and first-responder training needs must be updated as accidental spills, chemical fires and gas eruptions require different kinds of responses than brush and house fires.

-

Schools and Housing: There is the additional use of schools for families of drilling workers, and the impact of increased demand for rental housing, which drives up the price for local renters.

-

Infrastructure: Primary impact will fall on water systems, including municipal water, underground aquifer, individual wells, as well as ponds, lakes and rivers. Those impacts include water being pumped out of current water sources for use in the drilling process along with storage and disposal of retrieved fluids.

The Range of Planning Areas

The Range of Planning Areas

Having a clear picture of federal, state and existing regulations is critical. While every community may have unique requirements, the following is a shopping list of items for communities to consider. Site selectors should inquire about regulations such as the following when making a site choice, keeping in mind the ultimate goal of improved quality of life should they choose to plant roots in the community:

-

Inventories: A land and water inventory guide should be developed by collecting baseline data. Other communities with experience in hosting gas drilling say this is crucial to identify impacts to water, air, etc.

-

Impact Fees: Community impact fees for schools and roads should be implemented, e.g., assess taxes of number of trucks/day and weight.

-

Performance Bonding: Consider bonding requirements for pits and reservoirs. The fracking solution will either be trucked out or left to evaporate in reservoirs.

-

Special Licenses: There should be a special license to handle hazardous waste.

-

Holding Ponds: Require structurally reliable linings for the open pits that hold drilling water that contains various chemicals, biocides and fracking fluids.

-

Bonds Required: Evaluate mandated bonding to plug abandoned wells, which cost $15,000-$20,000 if there is no contamination, and can exceed $100,000 if there is a spill/contamination.

-

Monitoring: Require emission monitoring of road dust and ozone from flaring.

-

Set-Backs: Define mandatory setbacks from schools, houses, roads and streams as you would for any high impact industry or activity.

-

Storm Water: Enact storm water rules. Weeds and herbicides have presented problems in other states where gas drilling occurs. Since the federal government has exempted gas drilling from storm water runoff regulations, local governments should consider enacting their own storm water rules.

-

Watershed Ordinances: Carefully examine the development of municipal watershed ordinances. The industry could have three to 10 fracturing episodes for each well.

Useful Tools to Ensure Continued Positive Quality of Life

Local government may want to consider other options to ensure continued quality of life and, again, site selectors should inquire about them:

The Government GAP Analysis: First, recognize that only a few communities are truly prepared for major hydraulic fracturing play. An initial step for smaller communities and governmental bodies is a government GAP analysis.

The traditional retail GAP analysis illustrates the “gap” between products and services being purchased versus those being acquired locally. The difference is commonly known as shrinkage or “the gap,” and is measured in specific products/services and dollars “leaking” from the community.

Applying the same “gap” concept to a governmental structure delivers a specific picture in which external factors are driving the needs for specialized levels of governmental services. These are external factors over which local, county and regional governing entities have little control.

An example would be the rapid growth of construction classifications that require the full range of zoning, planning, plan check and project inspections. Staffing and the ancillary costs that accompany the construction planning inspection process are clearly needed, yet could well exceed the financial capacity of local government.

Further aggravating the scenario is the realization that, in the case of the extraction of shale oil and natural gas, the demand for such services will diminish over a period of years.

Further aggravating the scenario is the realization that, in the case of the extraction of shale oil and natural gas, the demand for such services will diminish over a period of years.

Utilizing a “Government GAP Analysis” will put into perspective those services needed by local government, but could be contracted or outsourced.

Comprehensive Economic Development Assessment (CEDA): The Comprehensive Economic Development Assessment (CEDA) provides communities with an analysis of its capacity to compete in the marketplace, as well as the capacity and effectiveness of its economic development infrastructure branding and marketing.

CEDA goes beyond the results of a singular study. It provides communities with a comprehensive and integrated picture of its key business components, areas of opportunities and implementation plan.

Community Drill Down: This type of in-depth analysis delivers the business information and intelligence necessary to address business retention and expansion (BRE) programs and economic gardening. The process makes it possible for local agencies and EDOs to:

- Identify existing companies located in a community and sort firms by a wide range of data search fields.

- Identify firms that may be at risk or vulnerable to closing, moving to another community and/or those ready to expand.

- Provide local agencies with the training and support necessary to initiate and execute an aggressive business retention and expansion program within the context of existing resources.

Community Visioning: This step is both a process and a product. The process gives residents, community stakeholders and appointed and elected officials the opportunity to identify key values of their community. From there, they can develop a consensus on what they would like to change or keep. The product is the roadmap that guides policy and resource allocation.

With a visioning process, participants take a realistic look at their community, not to assign blame, but to establish an honest appraisal of what their community is, define a collective view of where they want it to be in three to five years, and outline an action plan to get it there.

Why a Community Visioning project should be considered:

- A new industry has emerged that is or could change the fundamental structure of the community

- There has been a major shift in the population

- The overall community financial base has been impacted by a shift in the national, regional or local financial base

- There has been the loss or gain of a major segment of the employment base

Economic Gardening: Initiating programming that identifies and assists local and recruited entrepreneurs to start new businesses is a pillar of a sustainable local economy. New firms bring the highest value to the community in the long term, and make the best use of skill sets already possessed by the local workforce. It is cost-effective for communities to grow or recruit new businesses, but it does require expertise in business mentoring and coaching, both of which may be available through state agencies, or outsourced.

Business Retention: With the influx of new, well-paying jobs, communities frequently find it easy to forget the objectives of maintaining and growing existing firms. Job retention and social and economic stability are the results of a successful business development, retention and expansion program. Local governments should develop or outsource the development of reliable sources of information about local firms, and identify industry trends for key sectors of the existing local economy.

Business Retention: With the influx of new, well-paying jobs, communities frequently find it easy to forget the objectives of maintaining and growing existing firms. Job retention and social and economic stability are the results of a successful business development, retention and expansion program. Local governments should develop or outsource the development of reliable sources of information about local firms, and identify industry trends for key sectors of the existing local economy.

Conclusions

-

Local governments must have a clear picture of the impact shale oil and natural gas operations will have on the community’s physical and social infrastructure.

-

Given the scope of impact such extraction operations will have on a community and its limitation of resources and expertise, local communities should identify areas of common impact such as zoning, permitting, public safety, etc.

-

Where possible, operational and administrative processes should be standardized and streamlined through the use of web-based applications.

-

The use of joint assistance agreements should be developed to maximize obtainable, effective staffing resources. Such agreements could include purchasing, project inspection agreements, etc.

-

Intra-governmental communications and information sharing should be web-based and include both government-to-government and citizen-to-government channels.

-

Support and assistance for existing businesses should be centralized and recognized as a “core” priority. If resources are not available, outsource the task.

-

Workforce development and access to continuing education are critical to long-term economic stability and growth.

-

Job skills and labor needs assessments should be maintained as a priority.