|

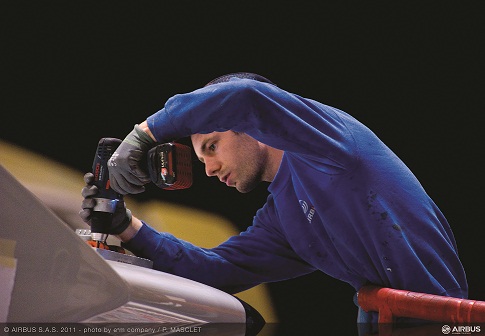

| Airbus S.A.S. 2012 - photo by e'm company/ P. Masclet |

In today’s environment, it is more important to find who can be held responsible than to simply solve the problem. Thus, the domestic workforce and businesses find themselves on different sides of the same coin, but dealing with virtually the same issue–finding good jobs and qualified people to fill them.

At its core, the issue of maintaining and advancing America’s competitive position with education, workforce and manufacturing, remains.

America’s Competitive Position

Over the next decades, America will experience an accelerating demand for increasing the output and quality of its education and workforce preparation systems.

The United States faces a future of slow population growth (0.98 percent per year) and even slower growth in the workforce (0.88 percent per year), as the population ages. The results will be fewer young entrants, equating to a smaller percentage of its population being available for the workforce.

It would seem that future tight labor markets would mean more employment and career options for the participants. However, the workforce would also be expected to meet the skill demands of a rapidly growing global economy. Additionally, it is also important to recognize that the smaller workforce share of the population will be made up of higher percentages of minorities, immigrants and low-income entrants with lower education and training preparation.

A secondary impact will be a significant escalation in the expectations of the new jobs. Global competition, new technologies and ramped innovation will pose significant challenges to both the definition and the level of education/skill preparation needed for employment security.

|

| Photo by Jeffrey Sauger for General Motors |

The rate of definitional change within industries, companies, jobs, skills and applications is accelerating. Independent of economic trends, the adequacy of traditional education and skill sets are shrinking dramatically. The economy will continue to redefine what basic, academic and technical education preparation will be required to adapt to the next wave of changes.

Fewer workers, who are less academically well-prepared, are faced with the demands of the workplace that exceed their level of education/skill preparations. Credentials, experience and loyalty no longer guarantee career success. The market increasingly demands higher competencies, in broader skill areas, and a workforce not only committed to, but capable of, continuous improvement. Even more significant to the individual, is the growing economic premium of higher education. The earnings gap between an individual with a high school diploma and Bachelor’s degree (BA) has doubled in the past 30 years. The chance of being unemployed for those with a high school diploma or less has almost quadrupled over the same period. The definition of economic security, standard of living and quality of life is increasingly dependent on the attainment of education and/or technical credentials beyond high school.

From a policy perspective, American social and economic policy has been based on a constant surplus of both skilled and unskilled labor. In the future, our policies must focus on the significant ramifications of growing shortages of skilled labor. This profound shift will necessitate a commitment to increase the level of education achievement of the traditional workforce while, at the same time, reaching out to those in our population who have traditionally been left behind by our culture and political system.

It is also important to recognize that the U.S. political leadership, government policies, education institutions and the public have been operating under the presumptions and rules of the old economy. They are generally unaware of these profound demographic and workplace shifts. They assume that the adverse economic conditions and employment opportunities they are experiencing come from unfair global competitors, low-wage foreign competition, non-responsive politicians, irresponsible business leaders and/or all of the above.

America’s competitive advantage in the new global economy will depend entirely on the quality (not quantity) of its workforce. The global pool of highly educated and skilled workers is growing and, will forever, increase the forces of competition on America’s companies and its workers. No President, Congress or law can make the changing world go away!

Perspective: The Post-Recession Workforce and Job Market

As the Country emerges from the recession, the economy will create more jobs than there are skilled workers available. The major growth will occur in fields where more advanced and ongoing technical training is required. Some growth in positions with mid-level skills will remain. These positions—a percentage of the workforce—along with unskilled, undertrained labor, are in serious decline. It is projected that roughly 87 percent of high-growth and high-wage jobs will require post-secondary education credentials.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) estimated that there was a shortage of seven million skilled workers at the end of 2010, and that number could grow to as much as 21 million by 2020.

|

| Photo by Alan Poizner for General Motors |

Summarily, there will be dramatic shortages of skilled and educated workers in manufacturing, energy, health care, technology, education and many other fields. These shortages will become more profound as the economy recovers and the education of the workforce continues to stagnate.

Perspective: The Employers

In a study initiated by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the University of Phoenix, it was indicated that 53 percent of employers say their companies face a significant challenge in recruiting non-managerial employees with the skills, training and education their company needs. The study’s results, summarized in Life in the 21st Century Workforce: A National Perspective, indicate agreement across both employers and employees that education (including continuing education and advanced degrees) is critical to ensuring workers have the skills necessary to advance in their professions. They also agree that interpersonal skills, collaboration, critical thinking and problem-solving are important to providing the most benefit to employers and the workforce alike.

"There is considerable discussion focused on the skills employees need to succeed in the workplace," said Margaret Spellings, senior advisor to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and former U.S. Secretary of Education. "However, it's imperative we understand the issue from the inside-out in order to improve the way we prepare our future workforce. The results of the study, Life in the 21st Century Workforce: A National Perspective, can help inform employers, employees and jobseekers seeking to stand out in the increasingly competitive job market."

Greg Cappelli, co-CEO of Apollo Group, parent company of University of Phoenix, comments, "Our nation is facing a critical disconnect between the skills our workforce brings to the job, and what businesses need. Despite the country's current unemployment levels, there are literally millions of jobs available for people with the right skills and the right education. We must look to the future and focus on providing students with a relevant education—one that prepares them with the expertise they need for successful careers in the workforce of tomorrow."

Among the key findings of the Life in the 21st Century Workforce study:

• Eight in 10 employers (80 percent) believe that education is critical to ensuring that workers have the competencies necessary to advance, and 72 percent of the labor pool agrees.

• U.S. workers believe that going back to school will have a direct impact on their career. The most common reasons for going back to school are to advance their career (89 percent), increase their salary (89 percent) or gain training for a specific job (88 percent).

• Employers believe that increasing the number of workers who complete post-secondary education programs and receive a degree or credential will contribute to the success of their company.

Perspective: The Employee

Perspective: The Employee

The speed with which changes take place in the workplace are impacting the worker in an even more dramatic fashion. The impact of the “education gap” in both unemployment and wages continues to grow at an alarming rate. In 1970, the unemployment differential between those with less than a high school diploma and those with a Bachelor’s degree was 3.3 percent. By May of 2009, it had grown to 10.7 percent.

Meanwhile, the wage differential of high school versus a Bachelor’s degree over 30 years has grown by almost 150 percent. The impact of the projected growth in high-skill jobs over the next 10 to 20 years will exacerbate these gaps further.

As global pressure grows, America’s employers continue to raise the hiring standards of basic, technical and academic preparation for new applicants. In addition, employers are looking for more than credentials. They are increasingly focused on demonstrated competencies, real-world application, related experience and preparation for new workplace cultures. The employment standard of tomorrow’s workplace is the demonstrated ability to adapt to the constant change in skill and application demands of the evolving workplace.

Perspective: Higher Education

The American public is growing increasingly aware of the personal premium that comes from higher education. That awareness is illustrated by the significant increase in the percent of high school graduates who enter post-secondary education within five years of their graduation, and the rapidly increasing number of adults entering community colleges, on-line universities and technical proprietary institutions. Also reflective of this growth is the very positive and clear presence of low-income and minority students who are desperately needed in the new workforce.

However, due largely to the failure of the K-12 system, higher education is experiencing vast increases in students who are less well-prepared for the rigors of post-secondary education. As a result, more than 40 percent of students in four-year colleges and 63 percent of students in community colleges are taking at least one remedial course.

Of those required to take a remedial course, only a small percentage ultimately graduate. Further, higher education graduation rates have now fallen with just over 60 percent graduating in six years. The low-income and minority students we need in our workforce fare even worse: 54 percent and 47 percent respectively.

Community colleges have experienced the greatest growth. Those enrolled students have found it particularly difficult to complete an academic or technical credential and/or successfully transfer to a four-year institution. These conditions are magnified by the increasing numbers of current workforce, low-income and minority students entering post-secondary education. These students are facing the challenge of overcoming non-credit-bearing remedial courses, regressive increases in tuition, impatience with traditional time to completion and a bewildering maze of course requirements not directly related to new economy and/or employer skill requirements.

New options from higher education are being demanded by traditional and non-traditional students. Higher education must recognize that the exponential demand for a skilled workforce, and increasing financial burdens, requires them to seek and identify new vehicles and conduits for the delivery of better and more relevant education.

Students and the business leaders are scrutinizing the timeline for acquiring a degree, the clear need for more contextual learning and a curriculum that is more aligned and relevant.

The Longer View

Many of the challenges identified are contrary to traditional academic institutional culture, and consistently meet resistance from management, faculty, administrators and/or staff.

Institutions and faculty senates must recognize that the fundamental social and economic changes as well as the opportunities they create are not options; they are realities. All higher education delivery systems will respond to both the changing environment and the expectations it spawns.

Higher education essentially has two fundamental choices: 1) try and catch up after the market has defined the new directions or 2) lead by taking the initiative, redefining the market, services, delivery mechanisms and dictating the outcomes for America’s future.