When it comes to the decision of where to locate and source manufacturing, it is clear that a new trend is emerging. The case for offshoring for cheap labor has lost much of its strength, and companies are now adopting a more comprehensive total cost analysis that often favors local sourcing. Based on the 284 published reshoring articles in the Reshoring Library, we calculate that about 50,000 manufacturing jobs have been reshored in the last two or three years. That surge represents about 10 percent of the total increase in manufacturing jobs since the low of January 2010.

When it comes to the decision of where to locate and source manufacturing, it is clear that a new trend is emerging. The case for offshoring for cheap labor has lost much of its strength, and companies are now adopting a more comprehensive total cost analysis that often favors local sourcing. Based on the 284 published reshoring articles in the Reshoring Library, we calculate that about 50,000 manufacturing jobs have been reshored in the last two or three years. That surge represents about 10 percent of the total increase in manufacturing jobs since the low of January 2010.

This need to adjust cost and sourcing models has evolved as natural disasters and political instability in many areas in the world expose the fragility in the extended supply chains. Other factors such as rising wages and currencies in low-labor-cost countries, soaring energy and transportation prices, and a suffering U.S. economy also play a role in the current shift in sourcing.

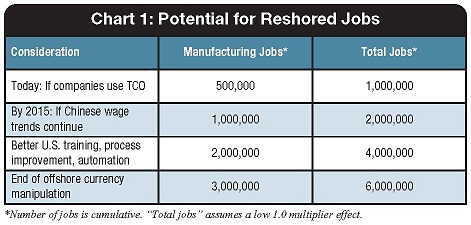

Total cost of ownership (TCO) is a key element in making better sourcing decisions. A TCO analysis helps to objectively identify the sources that minimize total cost, including those associated with the risk of additional supply chain shocks and disruptions. When all of the relevant costs and risks are taken into account, more companies are finding that manufacturing close to the point of consumption—"coming home," one might say—is the best choice. If the current trend of TCO use is paired with other favorable trend factors, the potential for reshored jobs is estimated at up to six million. See Chart 1.

Total cost of ownership (TCO) is a key element in making better sourcing decisions. A TCO analysis helps to objectively identify the sources that minimize total cost, including those associated with the risk of additional supply chain shocks and disruptions. When all of the relevant costs and risks are taken into account, more companies are finding that manufacturing close to the point of consumption—"coming home," one might say—is the best choice. If the current trend of TCO use is paired with other favorable trend factors, the potential for reshored jobs is estimated at up to six million. See Chart 1.

This shift is a promising sign for the American economy, workforce and individual companies. A new set of resources and perspectives is surfacing. The nonprofit Reshoring Initiative is one good resource for companies that want to objectively re-evaluate sourcing decisions. In addition to a Reshoring Library of published articles and a growing file of Case Studies, the Reshoring Initiative offers a free software program, the Total Cost of Ownership Estimator™, at www.reshorenow.org.

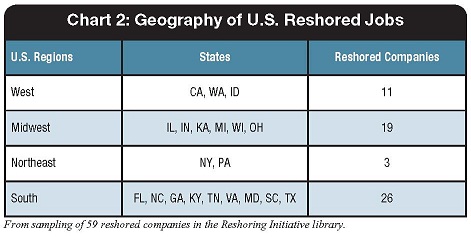

From the Reshoring Initiative’s library of published articles, we can see a regional breakdown of where reshored jobs are going. The top three states are California, North Carolina, and Texas. See Chart 2.

From the Reshoring Initiative’s library of published articles, we can see a regional breakdown of where reshored jobs are going. The top three states are California, North Carolina, and Texas. See Chart 2.

How to Calculate TCO

Total cost of ownership is a system for recognizing and aggregating all product costs including factors that are often overlooked in sourcing decisions. For example, it considers P&L costs such as travel for auditing, inventory carrying costs, obsolete inventory and "opportunity costs" associated with the inability to respond quickly and, even harder to predict, risk-related costs caused by political instability or natural disasters. The list of potentially relevant costs is long, but must be fully captured to provide a complete cost picture.

To determine the TCO with the TCO Estimator, the user assigns a value to each factor that is relevant to the specific case. The Estimator accumulates a single cost value for a product sourced from a particular supplier. The user then repeats the process, substituting other vendors. In this way, it is possible to readily and objectively compare the TCO for the same product from multiple vendors, whether local or offshore. The following list is a guide to the kinds of costs to include in the TCO, beginning with easily quantified, "hard cash" costs and progressing to more subjective measures.

1. Cost of goods sold or landed cost: This includes price, packaging, duty and planned freight, such as surface transportation, fees and insurance.

1. Cost of goods sold or landed cost: This includes price, packaging, duty and planned freight, such as surface transportation, fees and insurance.

2. Other "hard" costs: These include other costs that have an immediate effect on cash flow or are calculable and highly likely to occur.

a. Carrying cost for in-transit product. Foreign and local suppliers often are paid on different schedules. For example, Chinese suppliers often are paid prior to shipment, typically three to six weeks prior to U.S. receipt of the goods. U.S. suppliers typically are paid two to three months after the shipment date, which essentially is the same as the receipt date. In such cases, the customer's cash will be tied up for three to four months longer with an offshore source.

b. Carrying cost of inventory onsite. At the simplest level, the amount of onsite inventory will be dramatically higher for product shipped by ocean freight from offshore than for shipments from a local, ideally just-in-time, supplier.

c. Prototype cost. Many companies prefer to source prototypes locally so their engineers and marketing organizations can work intensely with the suppliers during product development. Local suppliers typically charge less for the prototype if they also receive the production orders.

d. End-of-life or obsolete inventory. When demand dies down or a product is revised or replaced, a company will end up holding some obsolete inventory. With an offshore source, the amount of inventory in-house, en route and on order will be higher than it would be with a local source, leaving companies that source offshore with more obsolete inventory.

e. Travel costs. The cost of ongoing auditing and problem solving is often overlooked, yet can have a notable impact on a product's total cost.

3. Potential risk-related costs: The cost impact of high-frequency risks, such as emergency airfreight, scrap and rework, to name a few, can be calculated based on past experience with an existing supplier. New products or new suppliers will require estimates. Other risks tend to have a low probability, but could still be devastating, so they should also be considered.

3. Potential risk-related costs: The cost impact of high-frequency risks, such as emergency airfreight, scrap and rework, to name a few, can be calculated based on past experience with an existing supplier. New products or new suppliers will require estimates. Other risks tend to have a low probability, but could still be devastating, so they should also be considered.

a. Rework. What costs incur when rework is required? These costs can be especially high for custom products, such as molds or dies.

b. Quality. Who pays for scrap? In addition to the cost of lost production and warranty-related payouts when the product fails, quality problems are costly in other, less-tangible ways. Think of the profit impact of lost market share, permanent loss of customers or the negative impact on brand image.

c. Product liability. How do the supplier candidates compare in terms of accessibility, willingness and ability to pay any product-liability claims? It can be difficult to sue a foreign company for damages, and even harder to collect.

d. Intellectual property risk. Approximately five to seven percent of world trade consists of counterfeit or pirated goods, according to the International Anti-Counterfeiting Coalition.1

e. Opportunity cost. What would be the cost of lost orders and customers when a supplier cannot respond quickly enough to changes in quantity or product specifications demanded by the market?

f. Brand image. What is the impact on brand image of the product's "country of origin" label? At a time when developed nations are continuing to experience economic instability and people are concerned about their jobs, consumers increasingly are buying locally made goods as a way to help the economy and their neighbors.

g. Economic stability of the supplier. It is much easier to investigate and find accurate information about the stability of a supplier located in the home market than it is for a supplier overseas.

h. Political stability of the source country. It's not difficult to rate the stability of countries that are already in chaos. It's much harder to correctly assess those that are making good economic progress but whose populations may be destabilizing because of changing consumer expectations and demands.

i. Exposure to another recession. The larger inventory and on-order quantities associated with offshoring represent an exposure risk if there should be another severe business downturn. Four months of inventory on hand, en route and on order could easily turn into much more in a recession.

4. Strategic costs: The following are just two examples of how sourcing decisions can affect product strategy and value.

a. Impact on innovation. U.S. companies have frequently been urged to offshore most of their manufacturing and focus on innovation and marketing. However, separating manufacturing from engineering degrades the innovative effectiveness of both a company and its home country, according to Harvard Business School (HBS) professors Gary Pisano and Willy Shih.2 Similarly HBS's Michael Porter has discussed the advantage for innovation of "clustering"—having suppliers, research universities, manufacturing and others involved in product development and production located near each other.

b. Product differentiation and mass customization. Many companies in developed economies are shifting their focus from commodities to differentiated products through mass customization, producing small quantities of products that conform to the specific desires of the market, but at costs approaching those of mass production. It is easier and less costly to make the move to mass customization with short, tightly clustered supply chains.

5. Environment: Finally, for each product source, a company should measure the "cleanliness" of the electricity generation at each location, pollution from the production process, the carbon footprint of its shipping operations, the requirements for local warehousing, how it disposes of obsolete inventory and other activities that affect the environmental impact of its supply chain. Once the "green" impact has been quantified for each source, the next step is to apply a dollar value to that impact.

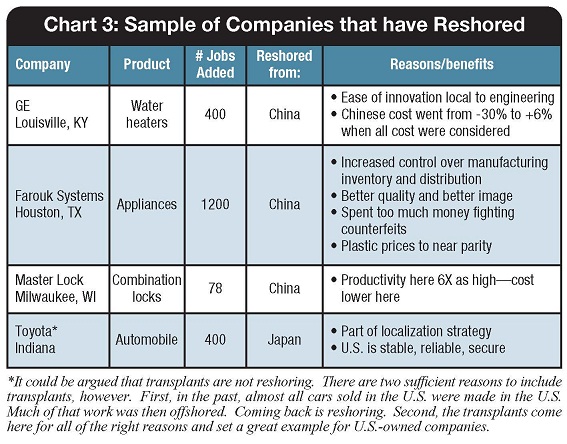

Chart 3 lists a small sample of the hundreds of companies that have reshored.

Chart 3 lists a small sample of the hundreds of companies that have reshored.

TCO helps relax some constraints on companies. When it becomes clear that there is not much difference between the total cost of ownership for locally manufactured and offshore products, it is easier for a company to place more emphasis and resources building strategies such as product-differentiation or brand-image strategy. A company might pursue local cost-reduction programs, such as lean, theory of constraints (TOC), design for manufacture and assembly (DFMA), quick response manufacturing (QRM) or automation that might have seemed insufficient to close the price gap before.

Adopting TCO makes good business sense. When companies understand their total cost of ownership they offshore less and reshore more. The government is getting involved, and so is everyone else, from the individual companies to educational institutions, Wall Street and consumers.

In January 2012, the White House hosted an impressive “Insourcing Forum,” highlighting TCO and reshoring in the lineup. As President Obama later summarized in the State of the Union, “…we have a huge opportunity, at this moment, to bring manufacturing back. But we have to seize it. Tonight, my message to business leaders is simple: Ask yourselves what you can do to bring jobs back to your country, and your country will do everything we can to help you succeed.” 3 The Administration has been very supportive of the Reshoring Initiative, with two reshoring pages (www.manufacturing.gov and http://nist.gov/mep/reshoring.cfm) already linked to the Initiative and a third scheduled for September on SelectUSA. Because reshoring is a win-win scenario for the public and private sectors of the economy, we expect to see further support develop. In the meantime, use of TCO is showing more companies that they can help both themselves and America by bringing production and service centers back to the U.S.

Sources

1 "Knock-offs catch on," The Economist, March 4, 2010.

2 Roger Thompson, "Why Manufacturing Matters," Working Knowledge newsletter, Harvard Business School, March 28, 2011.

3 “Management: How to Make It in America,” Quality Magazine, April 6, 2012